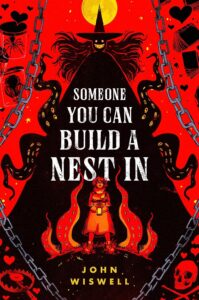

I’ve been reading John Wiswell’s short fiction for about four years now, and I’ve liked it enough to vote him to win the Hugo Award twice (sadly, the broader electorate did not agree with me in either case). So I was intrigued when I saw he was writing a novel featuring his typical wholesome subversion of horror tropes. But the description of Someone You Can Build a Nest In didn’t catch my eye enough to ascend the TBR, and I ended up waiting to read it until this year when it hit the Hugo shortlist for Best Novel.

Someone You Can Build a Nest In stars the shapeshifting, man-eating monster Shesheshen. After a chance meeting with the kindly, unloved daughter from a family of monster hunters, she finds herself hopelessly entangled in a hunt for herself, looking for an opportunity to reveal her true nature to her girlfriend in a way that doesn’t get her killed by the family.

Someone You Can Build a Nest In handles a couple themes that Wiswell has executed to perfection in previous short fiction, but they’re combined here in a way that never truly meshes, resulting in a story that’s trying to do something interesting but never really succeeds.

It starts with the misunderstood monster trope that was worked wonderfully in “Open House on Haunted Hill.” Despite having no qualms about eating people when the story starts, Shesheshen is written in a voice that’s quirky and naive, leaning hard into the wholesome, cosy vibe. While I do have complaints beyond the lead, I suspect that one’s enjoyment of the book as a whole will stand and fall on one’s appreciation of Shesheshen’s character. But unfortunately, her characterization never really clicked for me. Shesheshen’s voice bounces wildly back and forth between endearing naïveté and remarkably astute voice-of-the-author, such that she cannot fathom basic conversational norms but is wholly adept at identifying social subtext in a way that makes her sound like she’s had years of therapy. It’s an inconsistency that I could see other readers glossing quickly over because of the entertaining voice, but it’s one that I could never manage to overlook.

Additionally, Shesheshen’s monstrousness is minimized at every turn. Perhaps it should be no surprise that she sees herself as the heroine of her own story, but her struggles to fathom why humans fear her even though they eat meat and wear animal skins has the feeling of protesting too much. There’s never any real attempt to reckon with the dissonance between her actions and her self-perception; instead, she’s constantly humanized by the unrelenting dehumanization of the human characters—to the point that a bratty child raised by an abusive parent is portrayed as so villainous that a man-eating monster looks wholesome by comparison. The story hasn’t subverted the expectations of monstrousness so much as distracted from it by identifying a different, more monstrous monster.

That more monstrous monster feeds into the second major theme beyond the misunderstood monster romance: trauma recovery. “That Story Isn’t the Story” is probably the darkest I’ve read of Wiswell’s, and it is exemplary as a recovery story. Someone You Can Build a Nest In tries to hit the same notes while keeping the tone significantly lighter, and it just doesn’t come off the same way.

Part of the issue is that the traumatized character—the love interest from the awful family—doesn’t get any perspective segments, so we can only see her progression from the outside. She knows from the beginning that her family dislikes her and has treated her poorly, but she doesn’t understand the depth of the harm and still bears a sense of loyalty toward them. It’s a totally reasonable setup for telling a recovery story. But her on-page reactions to her family’s treatment barely scratch the surface of any emotional consternation that may lurk in the depths, and she is brought around to Shesheshen’s perspective remarkably easily. Her trauma story is clearly a major theme of the book, but it takes a backseat to the romance and the physical altercations for the majority of the story, making it feel like an afterthought. When it finally takes center stage in the final segment, there’s a rush to make up for lost time that just makes the whole subplot feel underdeveloped and poorly paced.

On the whole, I can see a lot of the themes that were on Wiswell’s mind when writing Someone You Can Build a Nest In, but the execution just doesn’t come off as well as in some of his short fiction. Shesheshen has a distinctive enough voice that she may redeem the book for some readers, but I struggled to look past the inconsistencies in her characterization. There’s still some writing skill on display here, and there are a couple scenes that show flashes of what this book could have been with a shift in tone or in the balancing of the themes. But mostly, it’s a bunch of intriguing pieces that don’t quite fit into a cohesive whole.

Can I use it for Bingo? It’s hard mode for Book in Parts and also fits LGBTQIA Protagonist, Book Club, and Parents.

Overall rating: 9 of Tar Vol’s 20. Two stars on Goodreads.