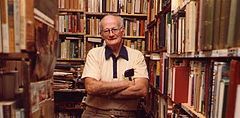

R.A. Lafferty, who died at 87 on March 18 [2002], was undoubtedly the finest writer of whatever it was that he did that ever there was. He was a genius, an oddball, a madman. His stories. . . are without precedent. -Neil Gaiman

Remember those old books for science fiction beginners, the ones that said “If you like Asimov , read Clement” or “If you like Sheckley, read Tenn”? And then you’d come to “If you like Lafferty, buy everything of his you can find before no one writes or thinks remotely like him.” -Mike Resnick

No true reader who has read as much as a single story by Raphael Aloysius Lafferty needs to be told that he is our most original writer. … Just about everything Lafferty writes is fun, is witty, is entertaining and playful. But it is not easy, for it is a mingling of allegory with myth, and of both with something more … In fact, he may not be just ours, but the most original writer in the history of literature. -Gene Wolfe

I usually read for characters first, plot second, and prose somewhere back in the distance. But there are two people in the world who constantly amaze me with their use of language. One is John K. Samson, a songwriter with a penchant for making the mundane poetic. The other, as you’ve no doubt guessed, is R.A. Lafferty.

If you’re a reader in 2021, there’s a good chance you’ve never heard of him. But there is a similarly good chance that someone among your favorite authors is a fan. And if you read their recommendations, one theme constantly recurs: there is no one in the world who writes like R.A. Lafferty.

Lafferty gets categorized as a science fiction writer mostly because his work sold best in science fiction magazines–and perhaps also because of praise from high-profile SF writers like Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke–but his stories have as much magic as they do science. His work is perhaps a cousin of New Wave science fiction, but it is as much a cousin of magical realism, and perhaps even New Weird. He’s influenced by science fiction and Greek and Roman mythology, but he’s just as much influenced by tall tales, Native American mythologies (Lafferty lived most of his life in Tulsa, Oklahoma), and Catholicism. Put it all together, and you have a writer who is uniquely himself, constructing both worlds and words like no one else.

I don’t think I should be getting more attention from mainstream book reviewers. I’ve never written any mainstream books, and I’m always surprised when the mainstreamers notice me at all. -R.A. Lafferty, from this tremendous interview

Short Stories

If you’re curious about reading Lafferty, the best place to start is with his short stories, which are arguably his best work and are undoubtedly his most accessible. While he thought that his novels had more to say and would reward rereading, his short stories wrote themselves.

The good stories, of course, write themselves. And somebody wants to know who are the really good writers, and how many of them there are. There aren’t any. Most of the writers are likeable frauds. Some are unlikable frauds. -R.A. Lafferty

The trouble is that the vast majority of his short stories are out-of-print. Fortunately, Neil Gaiman has pushed hard for reprintings of Lafferty’s stories, and we have seen two collections published in the last five years. [Incidentally, Neil Gaiman’s “Sunbird” is actually a pretty solid Lafferty pastiche, so if you read Fragile Things and thought “Sunbird” was the best of the bunch, you should absolutely dive headfirst into Lafferty.] Additionally, a handful of his older stories still survive in Project Gutenberg collections of old magazines with lapsed copyrights. So where to start?

- “Seven Day Terror” is one of the best places to start, and it’s available for free online (in addition to its place in the collection, The Best of R.A. Lafferty). It features the trademark joy and madness of Lafferty’s prose, as well as two other common themes: befuddled scientists finding themselves unexpectedly within a tall tale, and wild and precocious children that feel more like the children of J.M. Barrie than of any I’ve seen elsewhere.

- “Slow Tuesday Night” was nominated for a Nebula in 1966 and is a fascinating conceptual story that describes an eight-hour stretch in a world paced even faster than ours today. This is also collected in The Best of R.A. Lafferty

- “The Six Fingers of Time” may be as close to a traditional sci-fi story as Lafferty ever wrote, with a fairly straightforward temporal manipulation premise but all the flourishes that make Lafferty who he is. If you’re a science fiction reader and want to stick a little closer to your comfort zone, start here.

- The Best of R.A. Lafferty collects 18 of Lafferty’s finest stories, complete with 18 introductions written by Lafferty aficionados from Gaiman to Samuel R. Delany to John Scalzi to Connie Willis. This includes “Eurema’s Dam,” his sole Hugo Winner (which he personally considered inferior to five or six other stories he’d published the year before), along with a litany of favorites, from “Narrow Valley” to “Thus We Frustrate Charlemagne” to “Land of the Great Horses,” a story that expanded my view of what fiction could be like no other story before, and most likely no story after. Additionally, the collection includes some absolutely tremendous under-the-radar stories, like “Funnyfingers,” “Boomer Flats,” “Days of Grass, Days of Straw,” and “Thieving Bear Planet.” As I read Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation, I kept thinking that it reminded me of “Thieving Bear Planet” without the humor. So I was especially gratified to see VanderMeer’s name on the introduction to that particular story.

- There are plenty of other short stories floating around in out-of-print anthologies and old magazines. Two of my personal favorites, “Hog-Belly Honey” and “What’s the Name of That Town?” (with one of my favorite premises, in which scientists search for something known not to exist by examining the overwhelming evidence that it was never there) were left out of The Best of R.A. Lafferty, and while I understand that they had to make some cuts, I commend those to your reading if you’re able to find them.

Novels

Lafferty’s stories are easier to digest in small quantities, but that doesn’t mean he didn’t write some excellent novels. And if you’re reading this in 2021, you are much luckier than I was when I discovered Lafferty, because there are fresh reprintings of not one, but five Lafferty novels.

Okla Hannali

Okla Hannali–a mix of history, legend, and tall tale–is Lafferty’s epic account of the removal of the Choctaw people from their home in the Deep South and their rebuilding in the Oklahoma Territory. While Lafferty himself had no Native heritage, he seems to have avoided both the dual pitfalls of romanticization and racist stereotyping. Of course, I am no expert in respectful portrayal of Native cultures, but one of the experts had this to say in the foreword:

Anyone who has endured the milksop, watered-down, enwhitened view of Oklahoma history as taught in high schools all around Oklahoma is advised to read this book with extreme caution. Such readers are further enjoined to not be surprised to hear that there are indeed Indian versions of American history. Okla Hannali very handily provides such a version, and more of them are needed. -Geary Hobson

Okla Hannali revels in the joy of life, but it does not shirk the darkness. Lafferty spends chapters detailing the myriad injustices perpetrated against the Choctaw, but sometimes the most powerful statements are the shortest:

We review the bare bones of the affair. We hurry through the details of the uprooting. It’s a small matter to murder a nation, and these were but Five Nations out of hundreds. Three years, four, five, and most of it is ended. -Okla Hannali (on the Removal)

But amidst all the darkness, there is so much hope, displayed most prominently at the end in what is my favorite death scene in all of fiction. And there is so much rushing, racing joy of life, as evidenced in this delightful passage:

Everything was larger then,” Hannali would tell his son, “the forest Buffalo were bigger than the plains Buffalo we have now, the bears were bigger than any you can find in the Territory today you call that a bearskin on that wall it is only a dogskin I tell you it’s from the biggest bear ever killed in the Territory the wolves were larger and the foxes the squirrels were as big as our coyotes now the gophers were as big as badgers the doves and pigeons then were bigger than the turkeys now.”

“Maybeso you exaggerate” his son Travis would say.

“Of course I do with a big red heart I exaggerate the new age has forgotten how I remember that the corn stood taller and the ears fuller nine of them would make a bushel and now it takes a hundred and twenty and that doesn’t consider that the bushels were bigger…”

Fourth Mansions

I don’t recommend it often, because it’s a trip, and probably one that you either love or hate, but Fourth Mansions is one of the best novels I’ve ever read. Heavily inspired by Catholic mysticism, Fourth Mansions tells the tale of a young reporter who investigates a government bureaucrat who he suspects to be an ancient Egyptian returned from thousands of years in hiding and stumbles upon a conspiracy in which four supernatural groups vie for the soul of mankind. It is off-the-wall and amazing and also has some of the best chapter titles you will ever see:

I. I think I will Dismember the World with my Hands

II. Either Awful Dead or Awful Old

III. If They Can Kill You, I Can Kill You Worse

IV. Liar on the Mountain

V. Helical Passion and Saintly Sexpot

VI. Revenge of Strength Unused

VII. Of Elegant Dogs and Returned Men

VIII. The line of Your Throat, the Mercurial Movement

IV. But I Eat them Up, Frederico, I Eat them Up

X. Are you Not of Flimsy Flesh to Be so Afraid?

XI. “I Did Not Call You,” said the Lord

XII. Fourth Mansions

XIII. And All the Monsters Stand

Space Chantey

Perhaps the most accessible of Lafferty’s novels, Space Chantey is a joyful romp of a send-up of Homer’s Odyssey.

The war was finished. It had lasted ten equivalent years and taken ten million lives. This it was neither of long duration nor of serious attrition. It hadn’t any great significance; it was not intended to have. It did not prove a point, since all points had long ago been proved. What it did, perhaps, was to emphasize an aspect, sharpen a concept, underline a trend.

On the whole it was a successful operation. Economically and ecologically it was of healthy effect, and who should grumble?

And, after wars, men go home. No, no, men start for home. It’s not the same.

The Reefs of Earth

An delightful adventure that sometimes feels like an overgrown short despite length that sits along the border between novella and novel, The Reefs of Earth tells the story of six alien children (seven if you count Bad John), who try to make the world a better place by killing everyone else in it. They run into trouble when they keep saving everyone they meet for last.

If there were only six persons in the world (or seven, if you count Bad John), the Earth would be a much better place. All you had to do was kill all the other people on the Earth.

Lafferty has written plenty more tremendous work, but it’s much harder to find, so I will bring the squee to a close for now. But Lafferty is truly a gem, and it is long past time for him to undergo the same sort of posthumous rediscovery that rescued Philip K. Dick from obscurity. And now I really need to go re-read some Lafferty.